An artist whose career was tragically cut short, Howard Arkley (1951-1999) first became aware of the airbrush in 1969 in his first year at art school. He realised early on that he was not going to be a physical painter and the attraction of the airbrush was in being able to create an image without touching the surface. “I was never going to love paint and wallow around in it.” He said he wanted to make an image without getting his hands dirty.

According to Arkley’s biographer Ashley Crawford, Arkley absorbed the booming arts, punk rock and fashion scene of late 1970’s Melbourne in his art. The airbrush gave Arkley the opportunity to make marks quickly without using much paint and with little “physical involvement”. He agreed that what he was doing was going against the grain of painterly art that flourished in the 1980’s, in that he found the idea of mixing paint with turps and having the stuff “running down his arms” off putting.

Family Home 1993

So why the suburbs as his choice of subject matter? “They are my life, that’s where I grew up, my childhood, my formative years and this is what formed me both in my personal life and artistic life”.

Arkley was awarded the Alliance Francaise Art Fellowship, an artist’s residency in Paris in 1977 but he also visited New York and his experiences taught him that there could be a unique Australian urban art. He decided to use the suburbs as a cultural motif that had not been used before, and the wrought iron door with its flywire screen was the catalyst. The infinite variety of styles fascinated him and it gave him an avenue to explore an Australian artform divorced from traditional landscape art.

The repeated patterns in these doors formed the basis of later art including some abstract works, but more importantly in the depictions of the house itself where these patterns appear almost in abstract form, both in interiors and exteriors – he drew no distinction between the two. He saw patterns in houses, even those that contain no art at all and he didn’t want his art to be perceived as satirical.

Deluxe Setting 1992

When he spoke of inspirations for his work, Arkley reminds me a little of Andy Warhol. He often spent time in supermarkets buying products for no other reason than the design on the packaging, the dynamic use of colour and form. He also was influenced by art in the age of mechanical reproduction and he insisted that he wanted his paintings to look like reproductions, not the original, as though they had appeared in a book. Speaking of which, he also drew inspiration for his interiors from magazines such as House and Garden and from real estate advertisements.

He didn’t intellectualize about his art. He was a great gatherer of imagery and if he saw something that appealed to him, he would include it in his art.

Arkley had a love/hate relationship with suburbia “this suburban thing is in danger of swallowing me up, it’s a problem, and perhaps I should head for the You Yangs and get some relief.” It’s this love/hate relationship that kept fueling the fire “you can’t grab it and come to terms with it.”

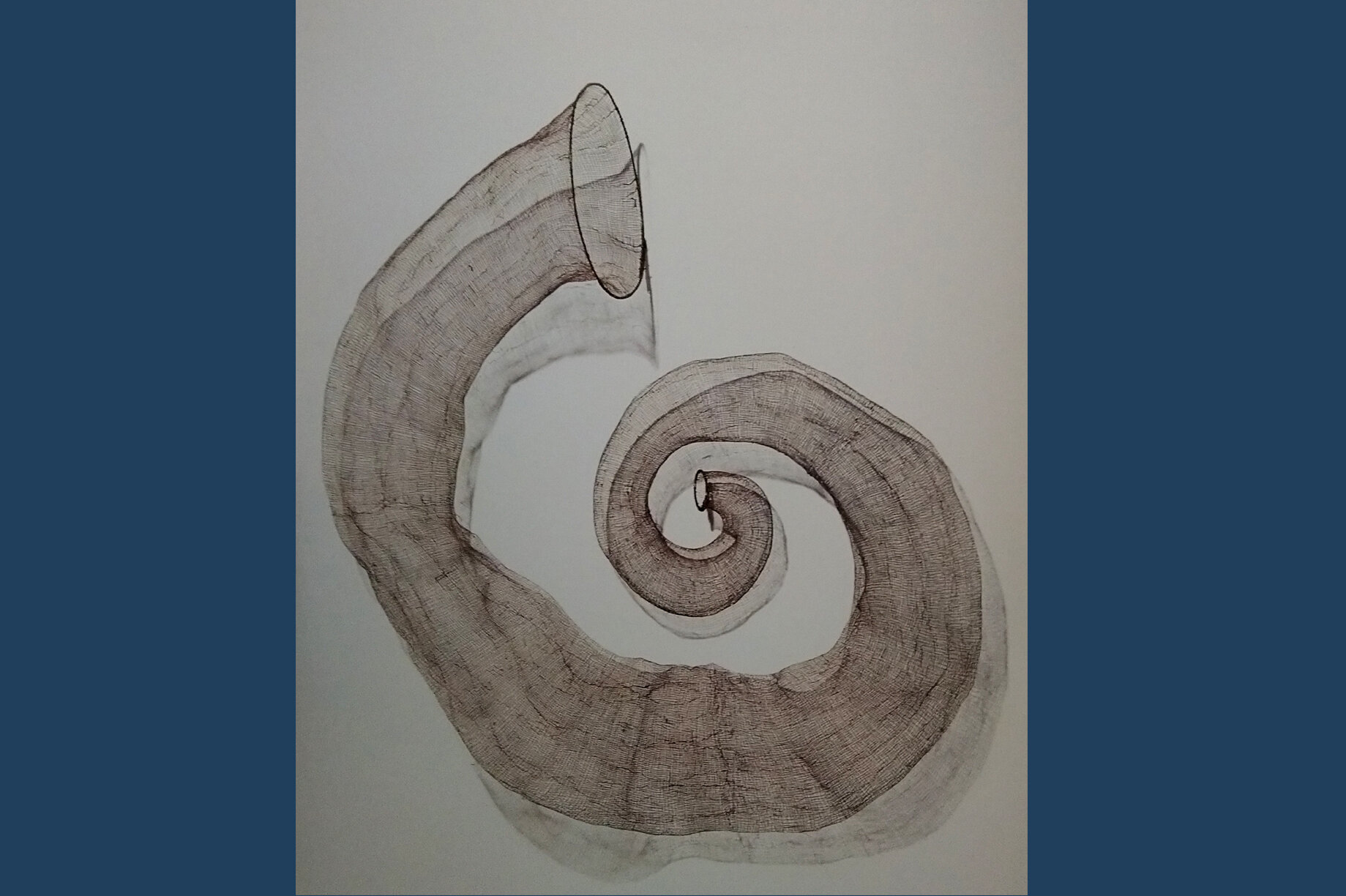

Freeway 1999

He was chosen as Australia’s representative at the Venice Biennale in 1999 and it was thought that the significance of his art was in breaking the mould of European perceptions of Australian art, and it was a great success. I saw the exhibition “Howard Arkley and Friends” at Tarrawarra Museum of Art a few years ago and it was a revelation with his bold use of colour and stensils that seemed to bridge the gap between abstraction and figuration.

Portrait of Nick Cave, a 1998 commission from the National Portrait Gallery

In his 1999 ABC interview, Arkley came across as a hard working, unpretentious person with a few surprises. “You go where your art takes you – it sounds romantic but I’m a romantic person.” But he also had his demons. His chaotic lifestyle was a concern to many of his friends and his addiction to heroin was a source of shame - he did his best to hide it. I can vaguely remember seeing an interview with him many years ago when he was clearly stoned and it was disturbing viewing. Shortly after the Venice Biennale, he had a sellout show in Los Angeles and then returned to Melbourne with his new wife Alison Burton. Just a few days later, he died of a heroin overdose aged 48.

Hello, my name is Geoff. You may be interested to know that I’m a fulltime artist these days and regularly exhibit my work in Victoria, but particularly in Melbourne. You may wish to check out my work using the following link; https://geoffharrisonarts.com

References;

Howard Arkley 1999 ABC TV

The Guardian

The Independent