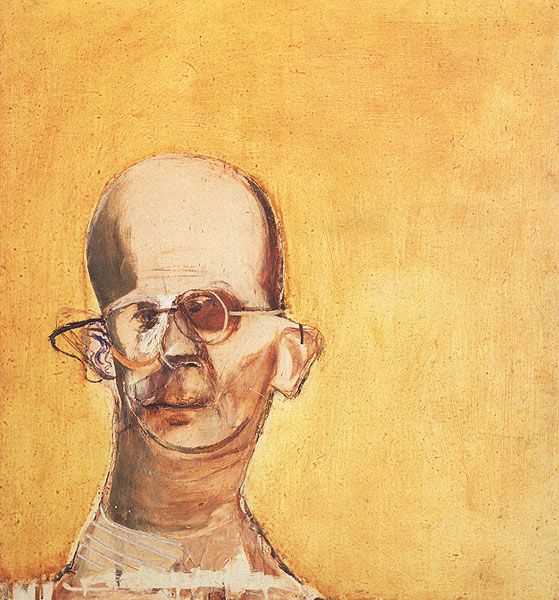

One Australian artist who appears to have slipped under the radar of many historians is Alexander Colquhoun (1862 – 1941), who was born in Glasgow and arrived with his family in Melbourne in 1876. Some time back, I posted about the landmark exhibition “Golden Summers” held at the National Gallery of Victoria in the mid 80’s which featured the Heidelberg School artists. Colquhoun wasn’t in it, even though he studied under Thomas Clark just like Fred McCubbin who was one of the ‘stars’ of the exhibition. And again just like McCubbin, Colquhoun was a member of the Buonarotti Club which was an artistic-musical-literary society in the 1880’s.

Portrait of Colquhoun by John Longstaff

I wasn’t even aware of Colquhoun until I saw an exhibition of his work at the Castlemaine Art Gallery in 2004. According to the gallery, this was the first significant exhibition of his work since his death. “As a writer and critic he did much to record the art history of his time and place. His writing, in books and in articles for periodicals and newspapers (including the Melbourne Herald and The Age), shows him to be a cultured man possessing a wide acquaintance with classical and general literature.”

Colquhoun - The Old St James Church 36 x 25 cm n.d.

Colquhoun took private students as well as teaching drawing at the Working Men’s College (later RMIT) from 1910. Later he taught art at Toorak College until 1930, as well as exhibiting regularly at venues including the Victorian Artists Society.

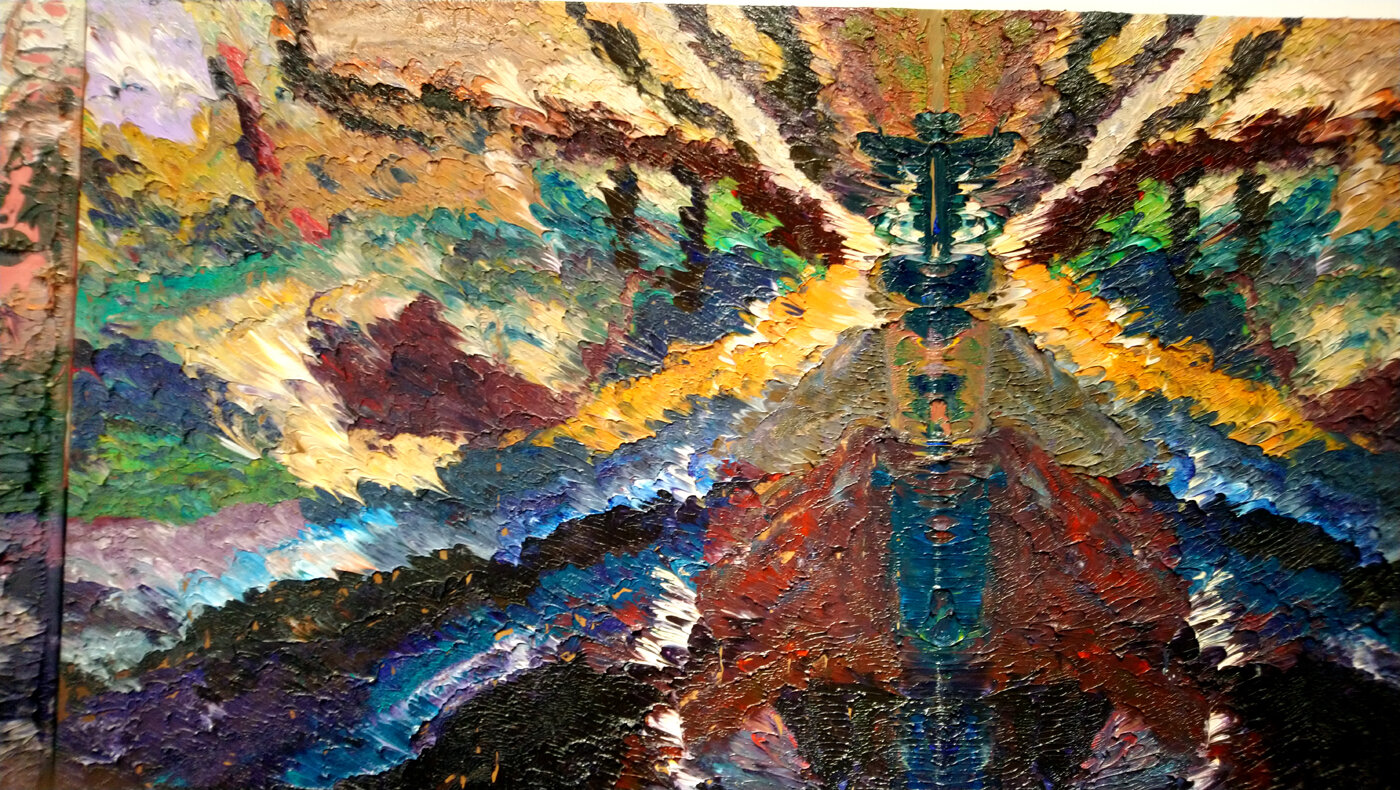

Colquhoun - A Spring Morning, 71 x 96 cm n.d.

He is not an easy artist to track down and some of his works are undated. He usually painted from nature using a sombre palette with some impressionistic accents, and most of his works are in oils either on wood panels or on canvas. Frederick Follingsby’s influence is apparent in Colquhoun’s early work. In later years he became friends with, was influenced by, Max Meldrum. His painting A Spring Morning has fetched the highest price of any of his works - $10,862USD in 2015.

Colquhoun - Figure In Interior, c1920

So why is Colquhoun so obscure? Possibly because he didn’t produce any blockbuster works such as Robert’s Shearing The Rams or McCubbin’s The Pioneers or Streeton’s Golden Summers. I think we can associate his darker tonal works to a later period when he fell under the spell of Meldrum. Some of his interior scenes remind me of nineteenth century social realist paintings by Jozef Israels and Honore Daumier but without the pathos. There is a calm domesticity, even intimacy in Colquhoun’s interiors.

Colquhoun - title and date unknown

In 1936 Colquhoun was appointed a trustee of the National Gallery of Victoria. He died in East Malvern in 1941, survived by his wife and three of their four children.

Members of the Buonarotti Club in 1885. From left, back row; John Longstaff, Llewelyn Jones, Colquhoun, E. Phillips-Fox, Fred McCubbin. Middle row; Tudor St George Tucker, Julian Gibbs, David Davies, Fred Williams. Seated at the front is Aby Alston.

Jane Sutherland was one of the first women to be invited into the Buonarotti Club.

References;

The Australian Dictionary of Biography

Castlemaine Art Gallery

The Heidelberg School – William Splatt and Dugald McLennan