I am making my way through Hannah Fink’s 2017 book titled “Bronwyn Oliver; Strange Things”, an expose on the life and work of the Australian sculptor Bronwyn Oliver (1959-2006). This book brought back fond memories of a major exhibition of her work held at the Tarrawarra Museum of Art in 2016. It was thought to be shameful that a decade after her suicide, her home state of New South Wales had not held a major retrospective of her work, and thus it was left to Tarrawarra – full credit to them.

Oliver's first exhibition at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney 1986

Oliver’s one time partner, the wine writer and critic Huon Hooke, wrote an effecting preface to Fink’s book. “My enduring image of Bronwyn at work is like this. She is sitting cross-legged on the floor, on a piece of foam rubber. Her work in on a low bench constructed of timber covered with fireproof bricks…..what happened in that studio I regard as some kind of fabulous, mysterious process in which bits of dull lifeless metal were transformed into beautiful objects full of wonderment, and the agent of that process was fire, delivered by a magic wand ”

She seemed to be happy only when working in her studio, and therein lies the problem. Only one day into her honeymoon with fellow artist Leslie Oliver at Narooma on the New South Wales south coast, Bronwyn got bored and suggested they “get back to work.”

Her sculptures have been described as hauntingly beautiful and are admired by major collectors and critics alike. She was a fiercely driven artist who disliked small talk and found social engagements difficult.

Curl/Schiaparelli, 1988, 80x80x25 cm copper

Oliver was always a high achiever. She was Dux of her high school and later was determined to continue her art studies overseas. She successfully applied for a scholarship for her master’s degree at the Chelsea Art School in London in 1982. Whilst there, she met Mike Parr and the two of them found they had a lot in common. Both believed that if they didn’t have their art, they would be “in deep trouble.” At one stage, she was sharing lodgings with the now renowned sculptor Anish Kapoor. They had long conversations together and she felt she needed to “get to know him better to understand myself as an artist”.

She also underwent counselling in London “it was mainly about Mum and me and my place in the family…and not worry about being defensive, threatened or over-sensitive” in social situations. She was rarely the easiest to get along with. When her husband Leslie spent 5 weeks in London with her, she expressed surprise at the strength of her dependence on him to confirm her feelings about the world, and the intense isolation she felt after he left. But it was also whilst she was in England that her 2 year marriage ended.

Unity, 2001, 100x100x15 cm copper

Never-the-less it was a highly successful 12 months in England for Oliver and, despite several job offers, she returned home where “I could make my own path, wherever I wanted to go.” Much of her early work featured fibreglass, cane and paper. Later she switched to copper and other metals.

During an interview with writer Maggie Gilchrist, Oliver was asked what her purpose was in making art. Her response was very revealing; “I am a loner. I’m not very sociable. It’s really the only way I have of communicating with people. I’m a social disaster when it comes chit chat or going to parties….This is the best way I know how to communicate my feelings about life. I am exploring the world when I make these. I’m putting my delight in how things are constructed, not just physically but all the unspoken structures….It’s my way of making sense of the world.”

Tarrawarra exhibition 2016

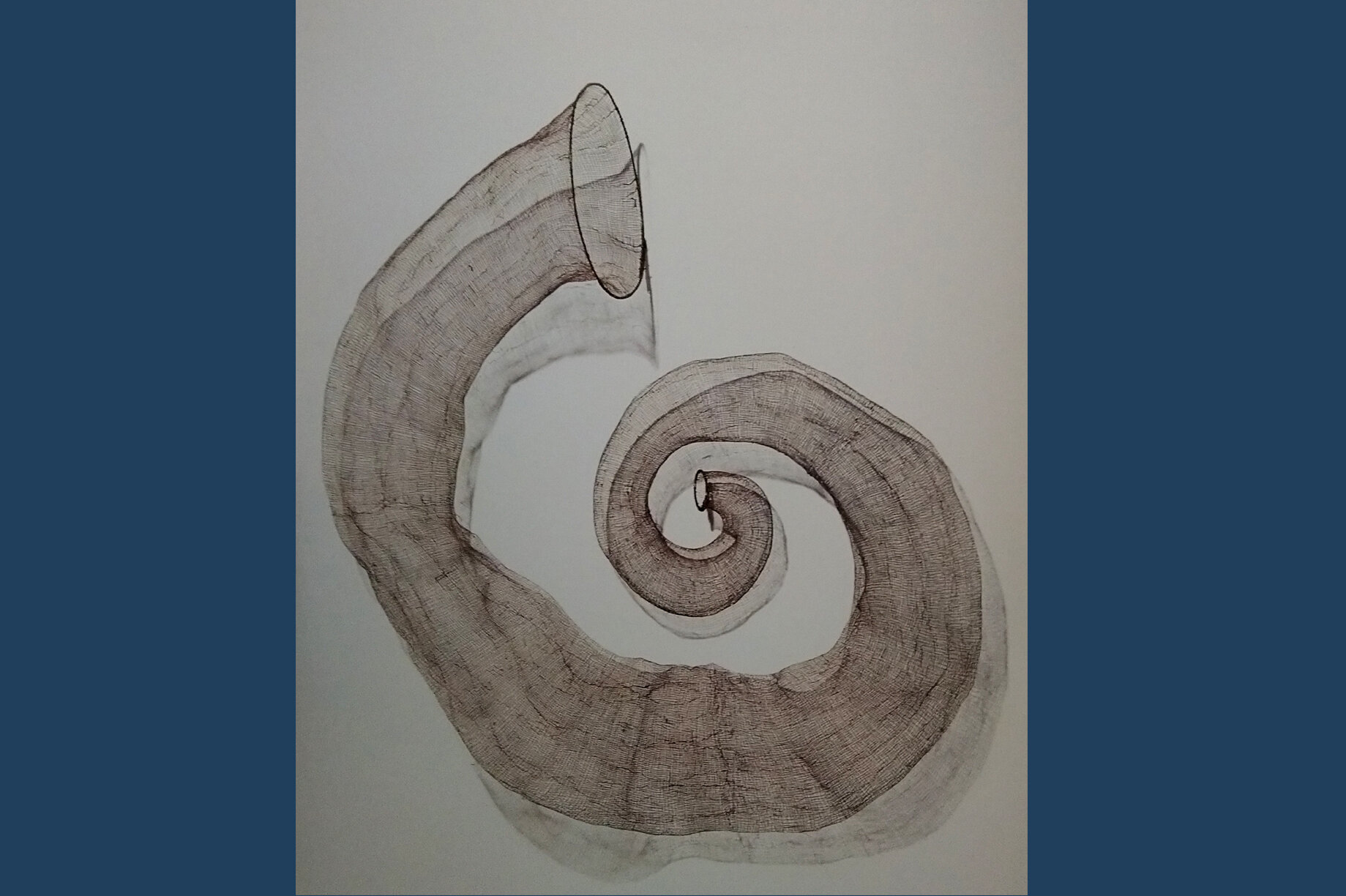

Oliver believed in the concept of space flowing through an object. “I was intrigued by the idea of enclosing space. If it can be enclosed and held, why not let it flow out and get away at the same time? Having both the inside and outside simultaneously visible in a way denies the physicality of an object. The openness is a kind of humble truth – nothing is hidden.”

Oliver strongly objected to any reference to handiwork in her art. She thought that referring to the craft aspect trivialized her intentions. The idea behind the work was paramount in the process of making her art. Fink believes some people underestimated the depth of her ambition, not for fame or accolades but for art of the highest order – for transcendence. She wanted her work to take on a life, a presence which was removed from this world.

Ammonite, 2005, 95x90x9 cm copper

“I am trying to create life. Not in the sense of beings, or animals, or plants, or machines, but ‘life’ in the sense of a kind of force, a presence, an energy to my objects that a human can respond to on the level of soul or spirit.”

Judging from what I saw at Tarrawarra, Oliver succeeded. There is an organic quality to her work, and yet an otherworldliness at the same time. I was drawn into her work, wanting to wrap my arms around some of them. The tactile nature of her work seemed in defiance of the materials used.

Between 1986 and her death in 2006, Oliver presented 18 solo exhibitions and from 1983 participated in numerous group exhibitions in Australia and overseas. She also undertook many commissions where she worked closely with clients and stakeholders, and for 19 years taught art to primary school students. In 1984 she won the Moet & Chandon Australian Art Fellowship. Her work can be found in public and private collections both in Australia and overseas.

Two Rings, 2006, copper

There are conflicting accounts of Oliver’s final years, but she was dogged by depression for most of her life. She once announced to a startled friend that she had divorced her family. Analysis of her hair following her suicide found extremely high concentrations of copper which may have exacerbated her mental condition. It’s thought that the breakup of her relationship with Huon Hooke (for which she blames herself) may have been the last straw. She hung herself in her studio amid newly completed works for an exhibition. She left no personal letters, only a note in a neighbour's letterbox for her former partner: "Please ask Huon to feed the cats."

Vine, 2006, copper. Hilton Hotel, Sydney

I am indebted to fellow Gippsland artist Jo Caminiti for talking me into visiting the Bronwyn Oliver exhibition at Tarrawarra. A memorable experience.

References;

Australian Financial Review

‘Bronwyn Oliver, Strange Things’, Hannah Fink, Piper Press, 2017

Tarrawarra Museum Of Art