We could have just ignored it, or laughed it off. But no, the contemporary art world had to tie itself in knots over Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain”, which was submitted to the Society of Independent Artists first exhibition in New York in 1917. Fountain is one of a series of “readymades” produced by Duchamp at the time.

Duchamp later recalled that the idea for Fountain arose from a discussion with the collector Walter Arensberg and the artist Joseph Stella. He purchased a urinal from a sanitary ware supplier and submitted it – or arranged for it to be submitted to the exhibition. The Society was bound by its constitution to accept all submissions, but it made an exception to Fountain. It was excluded from the exhibition and Arensberg and Duchamp resigned from the Society in protest.

‘Fountain’, 1917

The decision of the Society seemed to run contrary to its advertised ethos of “no jury – no prizes”. Duchamp had moved from Paris to New York in 1915, and with his friends Henri-Pierre Roche and Beatrice Wood wanted to assert the independence of art in America.

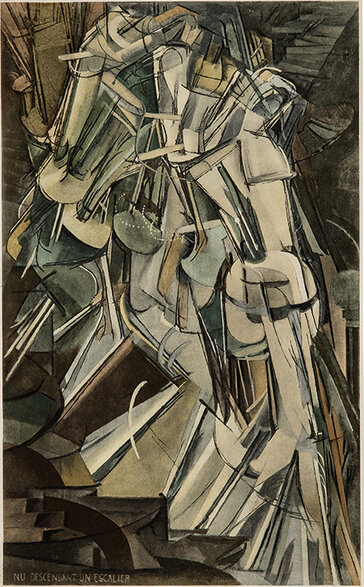

In its article, The Tate makes reference to Duchamp’s painting “Nude Descending A Staircase No.2” being withdrawn from the Salon des Indépendants in Paris in 1912. Duchamp apparently saw this as an extraordinary betrayal and described it as a turning point in his life. Thus, the submission of Fountain could be seen as an experiment by Duchamp in testing the commitment of the new American Society to the principals of freedom of expression and its tolerance of new conceptions of art.

‘Nude Descending A Staircase No.2’, 1912

So, what are we to make of Fountain? Was it part of Duchamp’s stated objective that anything can be a work of art if the artist says so? According to the Tate, the original is lost which begs the question why bother producing replicas of it and why is it considered one of the icons of twentieth century art? Artist Matthew Collings ask the question is Duchamp’s readymades all part of a ‘no skill is needed joke’?

“It was really trying to kill the artist as a God by himself” - Duchamp, commenting on Fountain. He was keen to remove the artist from the pedestal that he created for himself. Collings describes Fountain as the measure of all irony, now preserved at the Pompidou Centre in Paris – although copies can be found everywhere including any hardware store, come to think if it. Yet when I visit the sanitary section, I never think of Duchamp. Why?

“My idea was to choose an object that wouldn’t attract me either by its beauty or its ugliness, to find a point of indifference in my looking at it” - Duchamp commenting on his readymades. Collings sees Duchamp’s art as the first stirrings of avant-gardism in the 20th century, an avant-gardism that was not concerned with pursuing quality in art, but instead of quality. Collings believes Duchamp is responsible for the fact that no one really knows what quality is in modern art.

‘Bicycle Wheel’ - one of Duchamp’s Readymades

Duchamp’s first criteria for the art he produced was that it should amuse him, but then he thought it shouldn’t be what everyone else thinks art should be about – that is; the skill of the artist’s hand. He thought there should be something more – the artist’s mind was just as important as the artist’s hand.

In the 1960’s, just before he died, he was asked why when he wanted to destroy art, his readymades now seem so aesthetic and so part of art, he replied “well no one is perfect”. It’s argued that Duchamp opened the door to freedom in modern art, to feel free to do your own thing. Yet, Collings argues that Duchamp’s readymades are a devastating one-liner that has us questioning if we’ve reached the end of art. “Where can you go after that?” he asks. Duchamp’s answer was to play chess for many years.

Collings asks if Duchamp’s readymades are the sickly green light of cultures’ last meltdown. I like Collings’ description of Fountain being the asteroid of irony hurtling through artspace, a symbol of culture nowadays being empty and frivolous in the eyes of many. But he acknowledges the seriousness in Duchamp’s art too.

But Duchamp never gave up entirely on art, he just produced it secretively. An earlier blog of mine “The Woman Who Conquered Marcel Duchamp” discusses this.

References;

Tate.org.au

‘This is Modern Art’, BBC Channel 4, 1999 presented by Matthew Collings