Shortly before losing its arts channel to Foxtel Arts, SBS screened one of the best arts documentaries I’ve even seen. “Paris - the Luminous Years” is an American PBS production focusing on the years 1905-1930, “when for an incandescent moment Paris was a mecca, a magnetic centre of a new world of the arts, a laboratory of experiment and innovation. It attracted an international avant-garde and became part of the making of the modern”.

“If you succeeded in Paris, all doors were open to you” - Joan Miro.

(Perry Miller Adato)

All the arts are covered in this two-parter from 2010, performing and visual as well as literature. Suddenly the arts of the past, including impressionism seemed obsolete.

Origins

The so-called rebels of the arts were drawn to Mont Marte which was still semi rural in those days, high on a hillside and thus cut off from the rest of Paris. Artists crossed paths regularly, exchanging gossip whilst their favourite meeting places were just down the hill - the Lapin Agile and the Moulin Rouge.

(Wikimedia Commons)

They had their predecessors at Mont Marte of course, Van Gogh and Gauguin among them.

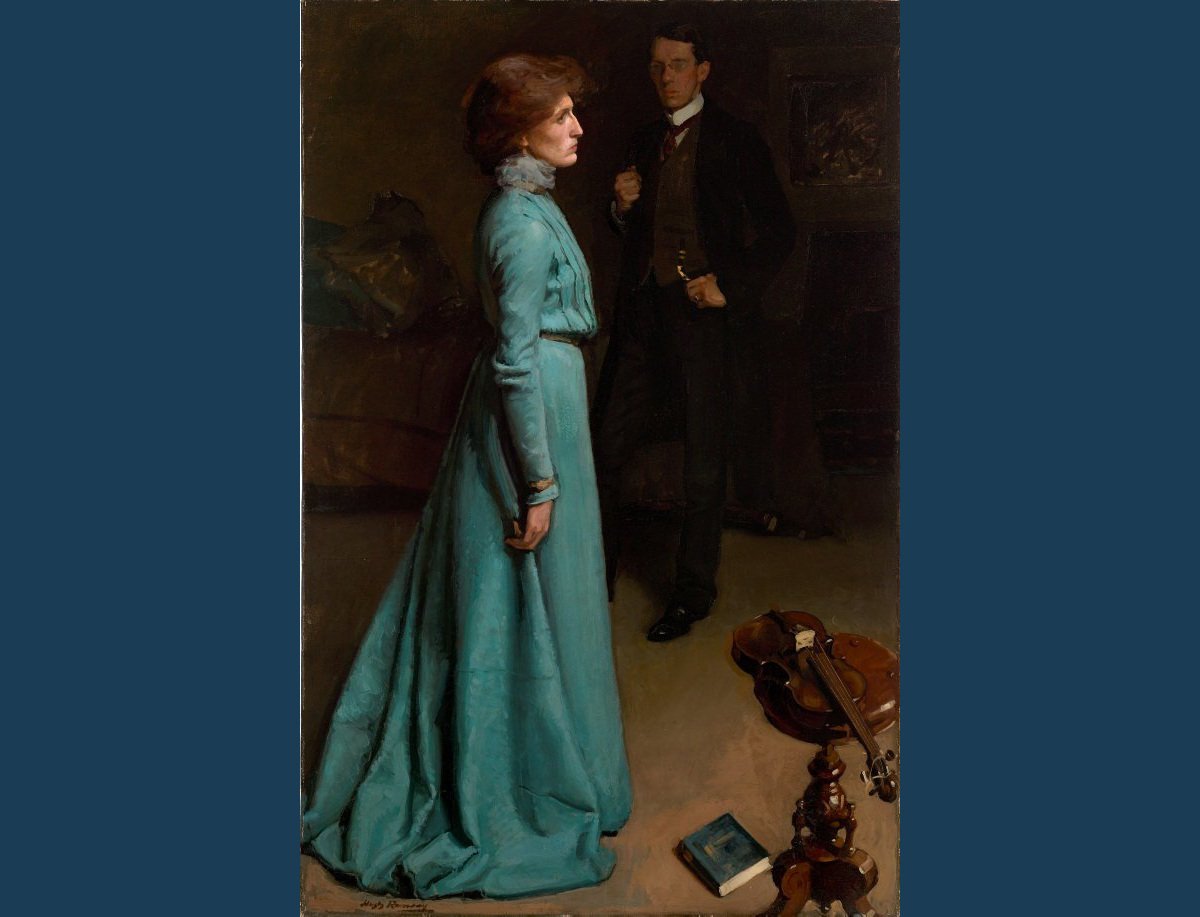

Major retrospectives of Gauguin in 1903 and Cezanne in 1907 in Paris had a considerable impact on artists of the period. Gauguin is considered the father of Fauvism, Cezanne the father of cubism. When Henri Matisse exhibited his ‘Woman With A Hat’ at the 1905 Salon d’Automne it was ridiculed by the public. Later, Gertrude Stein who was a collector of modern art, bought it.

Picasso's studio on the Rue Ravignan, (Wikipedia)

The Cafe

Pablo Picasso’s first studio was on the Rue Ravignan in Mont Marte from 1904-1910 where he shared lodgings with other artists and poets. Being short of cash, they appreciated the cheap rents and camaraderie. Picasso believes he really found himself as an artist during this period. Many artist studios and apartments of that era had no gas, no electricity and thus were freezing in winter. The cafe offered warmth, a cheap meal, a toilet, and an opportunity to sketch, write, plan exhibitions and gossip. Writers could find publishers and vice-versa.

Cafe Dome, Montparnasse (Wikipedia)

Artists and Poets

The “Picasso Gang” was formed in 1905 which included the poets Guillaume Apollinaire and Andre Salmon as charter members. With the exception of Georges Braque, poets were Picasso’s closest friends. Painters tend to have trouble explaining themselves and thus poets were useful in putting into words the artists’ objectives. Using his connections as an impresario and skill as a writer, Apollinaire was always willing to defend what was new and exciting in the arts. Apollinaire’s poetry acted as a clarion call to all avant-garde artists of that era.

La Ruche

Often referred to as the bee-hive, a communal space of over 70 studios near the slaughter house in Montparnasse occupied by Leger, Modigliani, Diego Rivera and others including painters and sculptors from Russia. In those studios lived the artistic Bohemia of every land, according to Marc Chagall. Many of the artists who practised at La Ruche had come from poor villages in Eastern Europe and beyond so poverty was not an issue for them. The artists of La Ruche didn’t identify with any “isms” of the era, they had no manifesto, instead they developed their own individual styles which were transformed by the experiences there.

La Ruche, Montparnasse (Pinterest)

Collaborations and Falling Outs

The close collaboration between Picasso and Georges Braque is covered. Braque once described the two of them as being like mountain climbers clinging to the same rope together. At one point, their work was almost indistinguishable. Then came WW1, Braque enlisted but Picasso didn’t, and that was the end of their friendship. Later Braque took exception to Picasso describing him as his ex-wife.

And then there was the falling out between the writers Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway. For some years each had been supportive of the others work in Paris, until Hemingway asked her to write a favourable review of a new series of his short stories in 1925. She was less than impressed and said so. Hemingway took exception to this and Stein responded “when a man writes continually about sex and death you can be assured that he is impotent, both as a man and a writer”. Ouch!

Ballet Ruse

The Russian impresario Serge Diaghilev brought his Ballet Ruse to Paris in 1909. With Igor Stravinsky’s scores, they reinvented the ballet. Diaghilev brought together dancers, writers, composers, musicians, choreographers and artists (including Picasso who designed some of the sets for his productions) and is considered one of the most influential figures in the art world at the time.

World War One - the Aftermath

The war tended to alienate those artists who enlisted from those who didn’t. It’s argued that the war gave the conservative right in French society the opportunity to rail against avant-garde art by portraying it as German. Avant-garde artists grew concerned that anything they produced that couldn’t be readily understood might be interpreted as German inspired. The paint on their cubist works had barely dried before they began churning out conservative portraits. A neo-classical movement had arisen - lead by Picasso. To make matters worse for them, the main dealer in cubist works, Daniel H. Kahnweiler (a German) was forced into exile. Apollinaire served in the war and was badly injured before dying of the Spanish Flu two days before the armistice was signed in 1918.

Paintings by Robert Delaunay from 1912 (left) & 1914 (Wikimedia Commons)

Among the more significant art movements that arose in the early 1920’s was Dada, a protest movement born out of the horror of the First World War. It was subversive and provocative and it eventually evolved into Surrealism. The contribution of Marcel Duchamp is discussed with his ‘readymades’ leading to a never ending argument about what constitutes art.

The Americans

Many American writers who had served in Europe during the war returned to Paris in the early 1920’s and were inspired by the freedom, the mood for experimentation and the art of Picasso (back to his cubist phase again) and others. This was in marked contrast to the repression, censorship and prohibition that constituted life back in the States - all the things they had fought against in Europe. So it was little wonder that they couldn’t get back to Paris quickly enough. And life was so cheap, you almost didn’t have to hold down a job to survive.

American women artists and writers found particular freedom in Paris compared to life in the States where they were expected to marry young and raise families. American jazz represented modernity to the French and it had a major influence on French composers and artists.

Matisse, Woman With A Hat, 1905 (Wikipedia)

Serge Diaghilev died in August 1929 and the Ballet Ruse would close shortly after. Two months later came the Wall Street crash, the effects of which would reverberate across Europe. It would devastate the avant-garde in Paris and most expatriot American artists would return home. Eventually Braque and Picasso would reconcile - to a point.

This documentary includes interviews with academics, art historians and contains archival footage of interviews with Joan Miro, Marc Chagall, Jean Cocteau, D. H. Kahnweiler and many others. If there is a criticism I could level against this series, it’s that there is no mention of the artists who didn’t make it and what became of them. Perhaps there is a tendency to romanticize the era to some degree.

Hello, my name is Geoff. You may be interested to know that I’m a fulltime artist these days and regularly exhibit my work in Victoria, but particularly in Melbourne. You may wish to check out my work using the following link; https://geoffharrisonarts.com